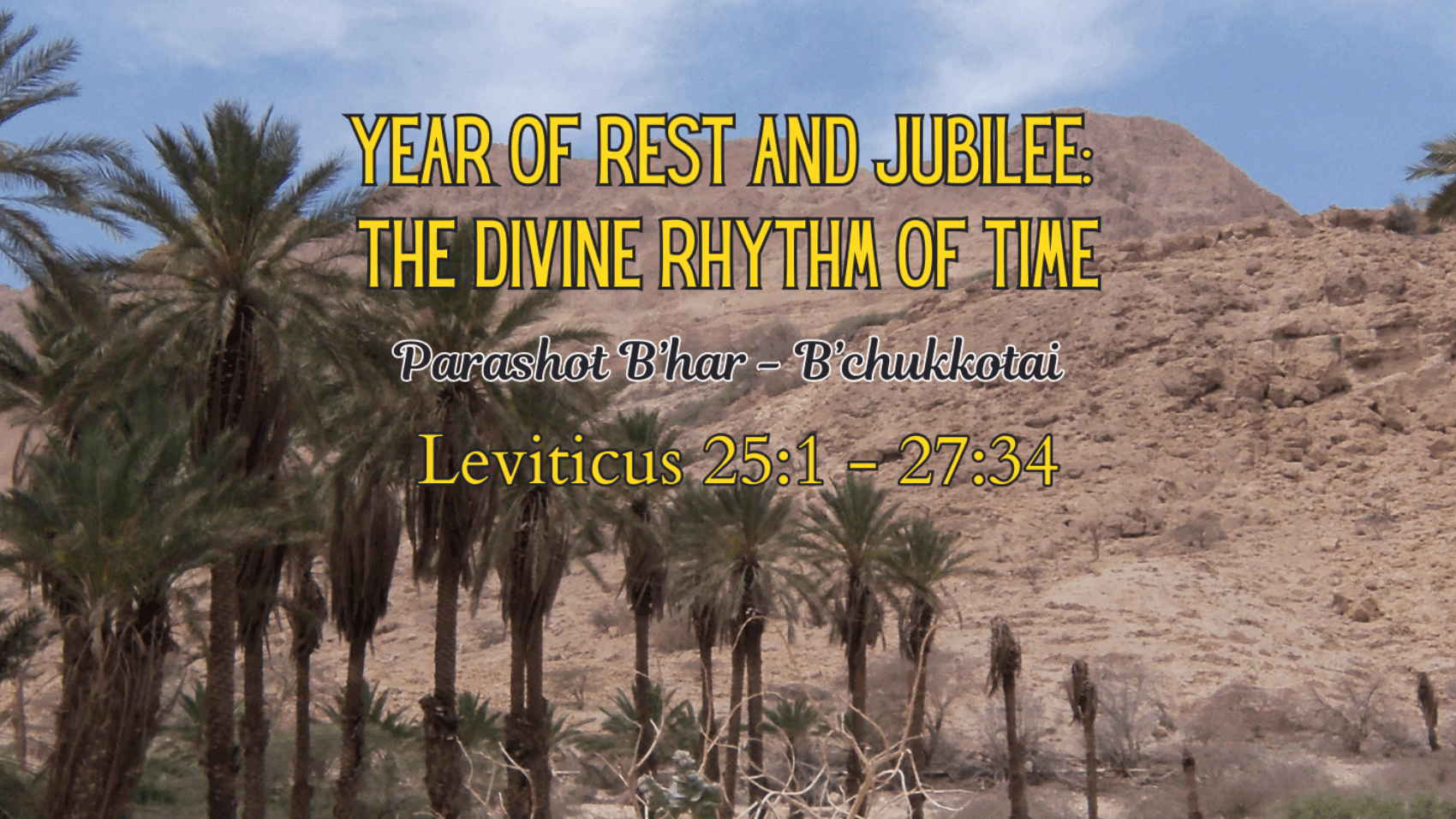

Parashah B'har

Leviticus 25:1 – 26:2

The parashah BeHar, found in the book of Leviticus, means “on the mountain.”

All of these instructions, which began when Moses ascended Mount Sinai after Yehovah declared the Ten Commandments in Exodus 20, continue throughout the book of Leviticus, as the Israelites spent over a year camping at the base of Mount Sinai.

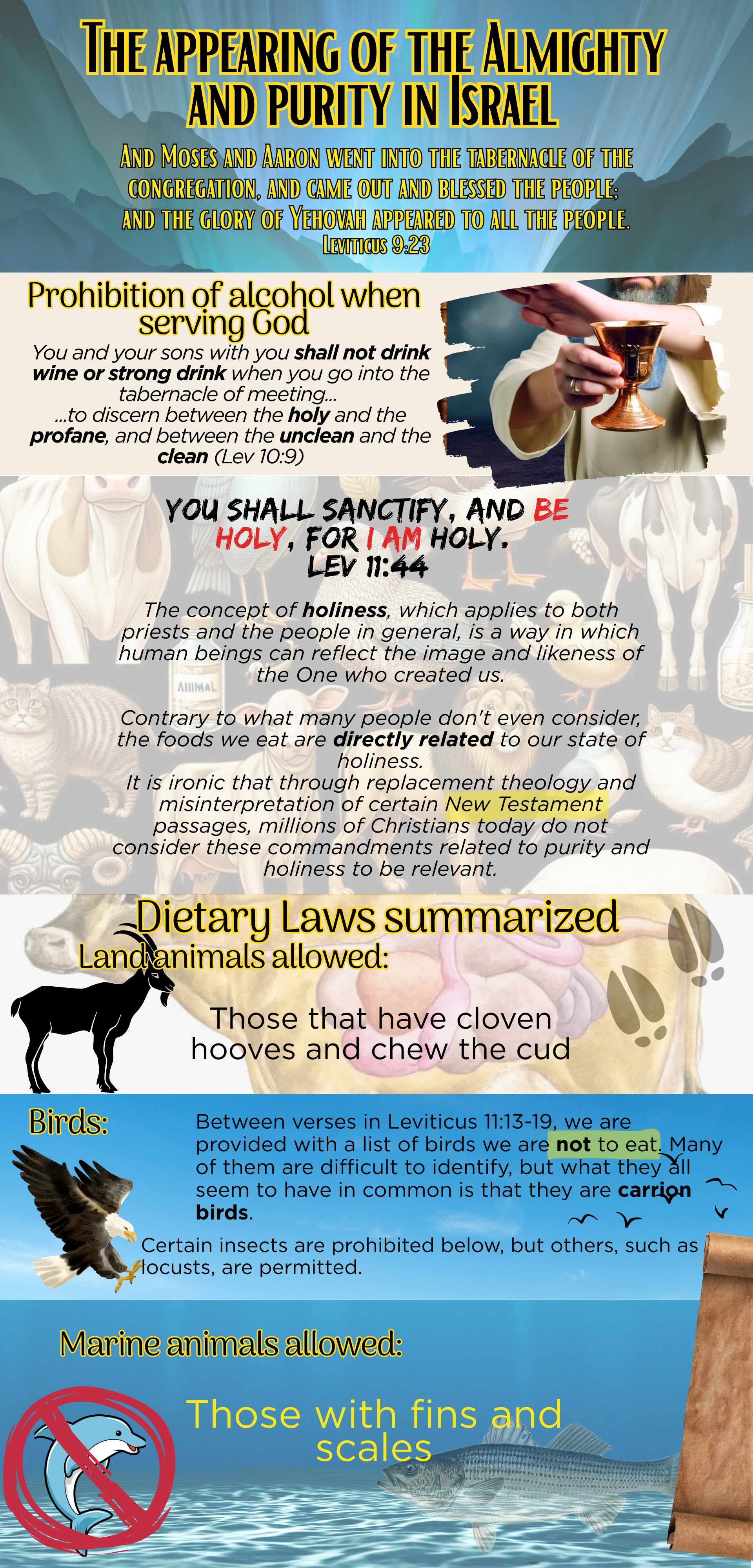

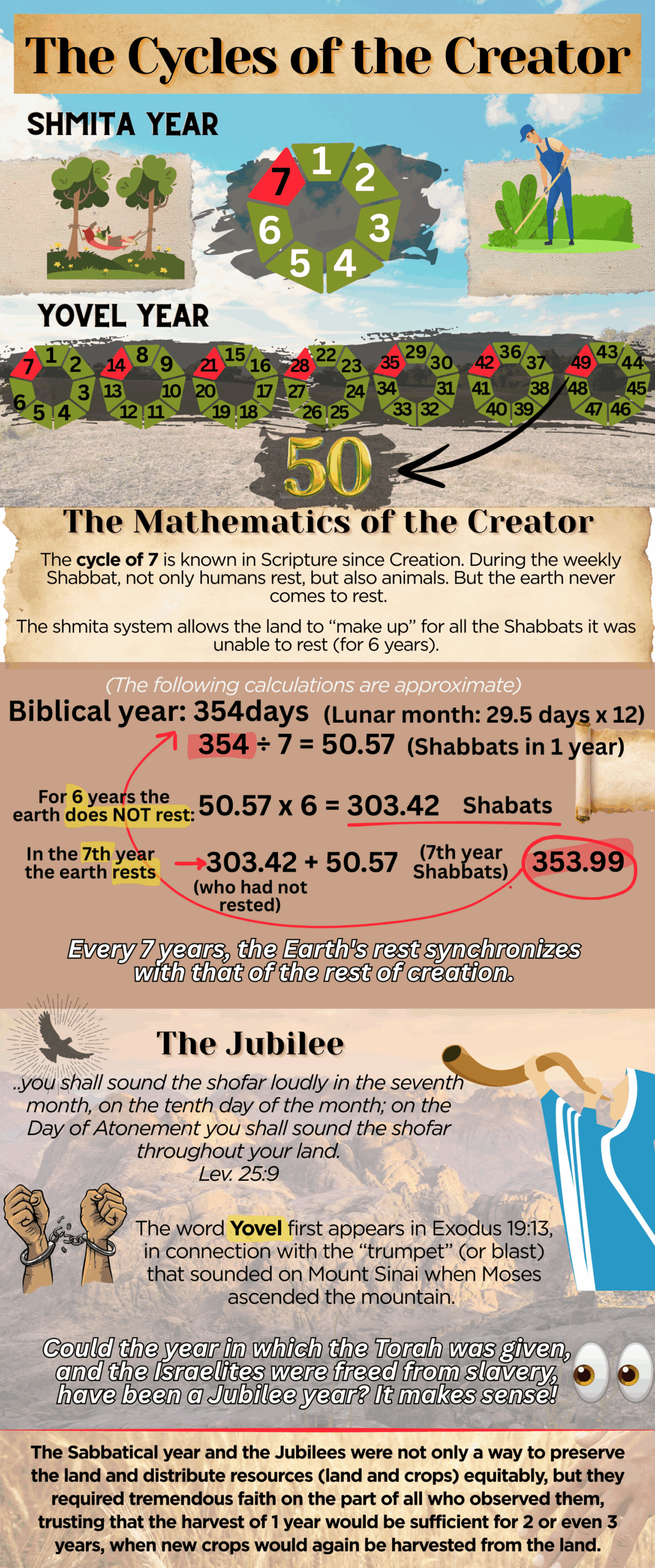

This portion introduces one of the most revolutionary and spiritual concepts in the Bible: The Sabbatical Year, or Shmitah, and the Jubilee Year, or Yovel. This commandment, Shmitah, which mandates that the land be allowed to rest every seven years, not only has ecological implications, but also has profound implications for faith, social justice, and the relationship between human beings and the Creator and His Creation.

The Jubilee year also heralded the return of all inhabitants to their ancestral lands. That is, even if the lands were sold and accumulated by certain individuals or families, at the end of this period there was a “great reset,” in which everything was restored and a new beginning took place. Through these actions and observances, the inhabitants of the land were to recognize Who was the True Owner of all the land.

Miguel Forero

May 22-2025 - Leviticus

Parashah B'chukkotai

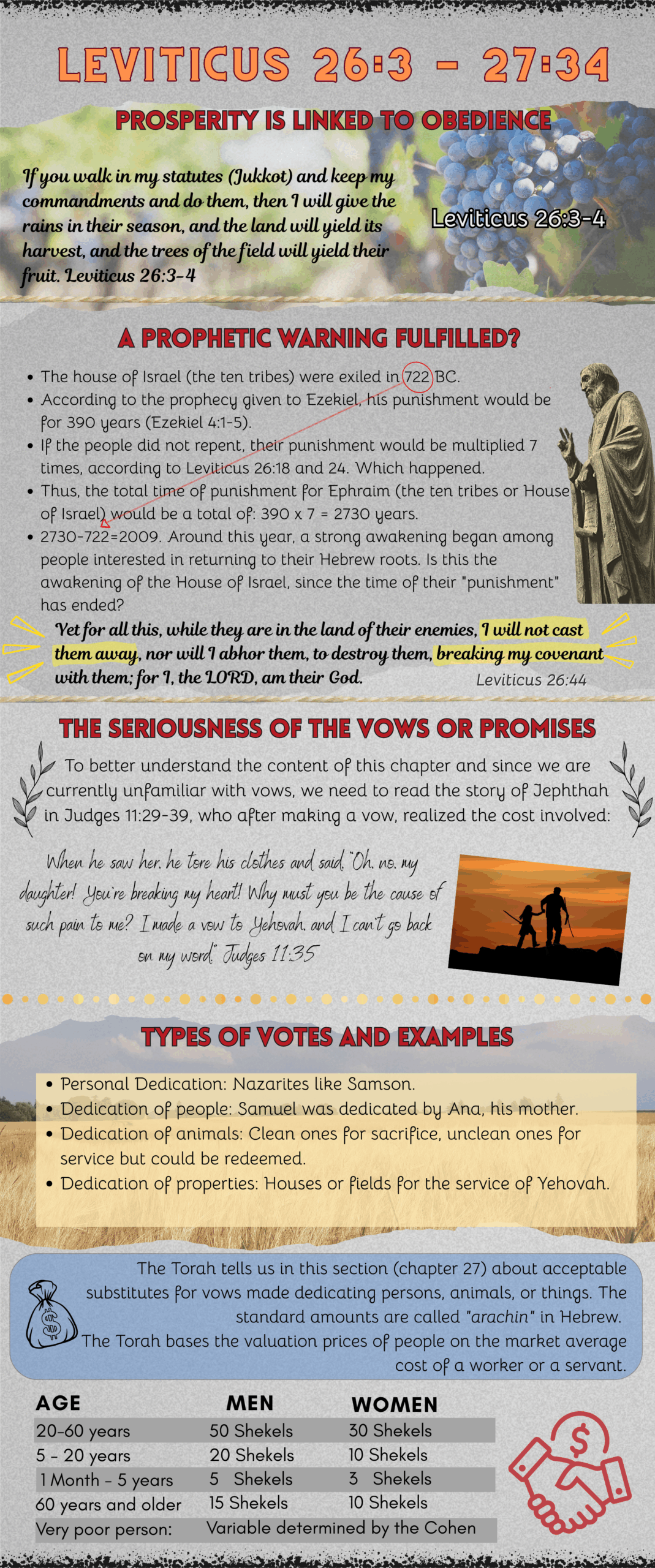

Leviticus 26:3 – 27:34

This last portion of Leviticus deals with the blessings that result from obedience as well as the curses that come with disobedience.

Yehovah our Father has the legal and total right to demand that His creatures obey the commandments He establishes, for many reasons:

- He is the Creator of the Universe.

- He is the Sustainer of life.

- He is the One who rescued Yisrael from slavery (including us) with great and powerful signs.

- He is the One who made a covenant with Yisrael after He had already given them freedom.

Despite all of the above, our Father Yehovah does not force His people to obey His Torah (instructions or commandments), but rather gives us complete freedom to do so, because He expects the act of obedience to be a demonstration of love and gratitude, rather than simply an act of submission.

Let us pay attention to the advisability of obeying, because there are blessings that come from doing so; this is how His Creation is designed. He is not a policeman lying in wait to catch those who break the law so He can “come down” on them with a curse. NO! Simply, our decisions have “natural” consequences that will unfold according to the actions we take.

The issue of vows is complex for us, as they were directly related to the existence of the House of Yehováh (Temple) and the cohanim (priests). A person could have made a vow in a time of difficulty, but then find it impossible to fulfill it. Then there was the possibility that they themselves or someone else would pay a certain amount to, in a sense, “undo” that vow, and so a value was established depending on the person’s condition and age.

The question arises: can we make vows today? Not the kind that were made in the days when the House of Yehovah was standing. But we could commit ourselves to do or not do something with a view to honoring our Father and improving our condition as human beings. Only, in doing so, let us keep in mind what Scripture itself tells us:

Better is it that thou shouldest not vow, than that thou shouldest vow and not pay.5 Suffer not thy mouth to bring thy flesh into guilt, neither say thou before the messenger, that it was an error; wherefore should God be angry at thy voice, and destroy the work of thy hands?6 For through the multitude of dreams and vanities there are also many words; but fear thou God. Ecclesiastes 5:4-6 (CJB)