Parashah BeHa'alotkha

Numbers 8:1 – 12:16

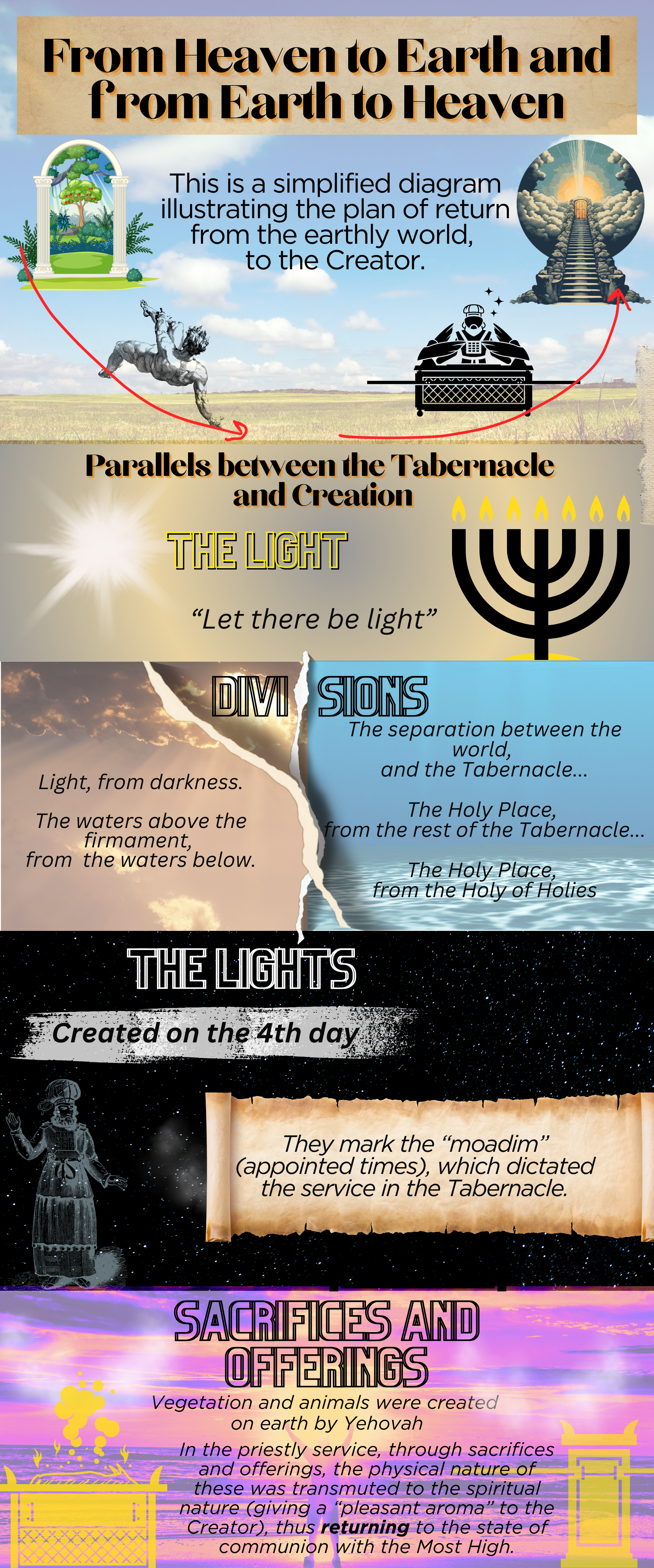

A very relevant event is recounted in this Torah portion; in the second year, in the second month, the children of Israel departed from the wilderness of Sinai (Num 10:11). The previous month (the first month of the year following the Exodus), the Tabernacle had been erected (an event originally recorded in Exodus 40 but recalled again in this parashah, in Num 9:15).

The people of Israel, having been freed from slavery in Egypt, had a supernatural encounter with the Almighty on Mount Sinai. There they remained for almost a year, even several months after they had received the Torah through Moses. The main reason they stayed there was to materialize the commandment to build the Tabernacle.

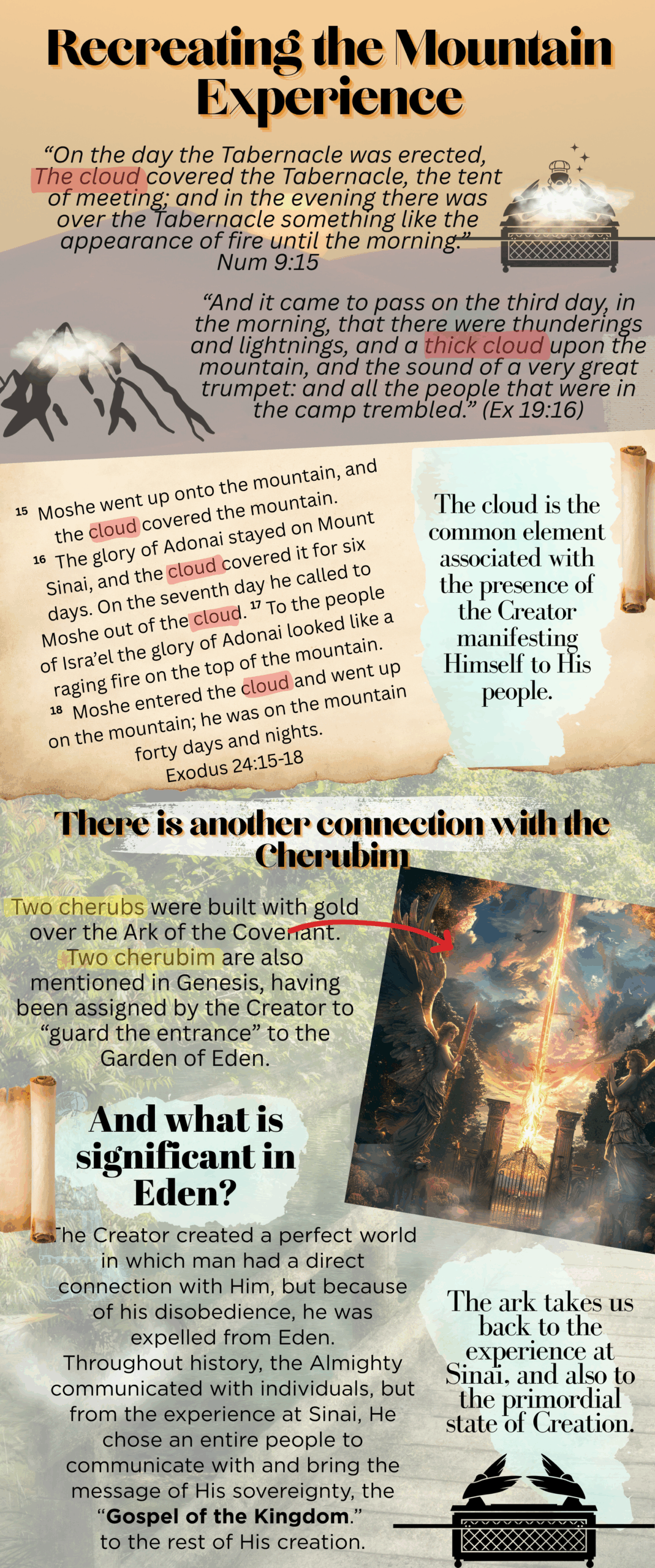

The Tabernacle was to become the portable experience of Mount Sinai for the children of Israel for generations to come. The Ark of the Covenant, also called the Ark of the Testimony, would carry with it the cloud that all the people witnessed at Sinai. The same cloud that guided the Israelites in the wilderness for forty years.

The connection between the cloud, the Ark of the Covenant, and the experiences at Mount Sinai and the Garden of Eden shows us the continuity of divine guidance and protection throughout biblical history. According to rabbinic commentators such as Rashi, the cloud not only provided physical guidance, but was also a symbol of the constant and protective Divine Presence (Rashi on Numbers 9:15). This narrative invites us to reflect on the importance of relying on divine guidance in our own spiritual journey.

Questions for reflection

1. Trust in Divine Guidance: In what areas of your life can you learn to rely more on divine guidance, just as the Israelites relied on the cloud and the Ark?

2. God’s Continuing Presence: How do you experience God’s presence in your daily life? What practices help you feel that presence more tangibly?

Symbolism of the Cherubim: What meaning does the image of the cherubim over the Ark of the Covenant have for you in relation to divine protection?

4. Lessons from Sinai: What lessons can you apply from Moses’ experience on Mount Sinai when he ascended the cloud to receive the Law?