Parashah Shoftim

Deut 16:18 – 21:9

One of the most prominent features of Parashat Ki Tetze is its extensive list of laws—seventy-four of the six hundred and thirteen, to be precise—ranging from conduct in times of war to the proper handling of stray animals. Among these laws are the following:

The rights of captive women (Deuteronomy 21:10–14)

The treatment of rebellious sons (Deuteronomy 21:18–21)

Regulations concerning lost and found property (Deuteronomy 22:1–3)

Laws regarding the fair treatment of workers and animals (Deuteronomy 24:14–15)

Leaving portions of the harvest for the poor (Deuteronomy 24:19–22)

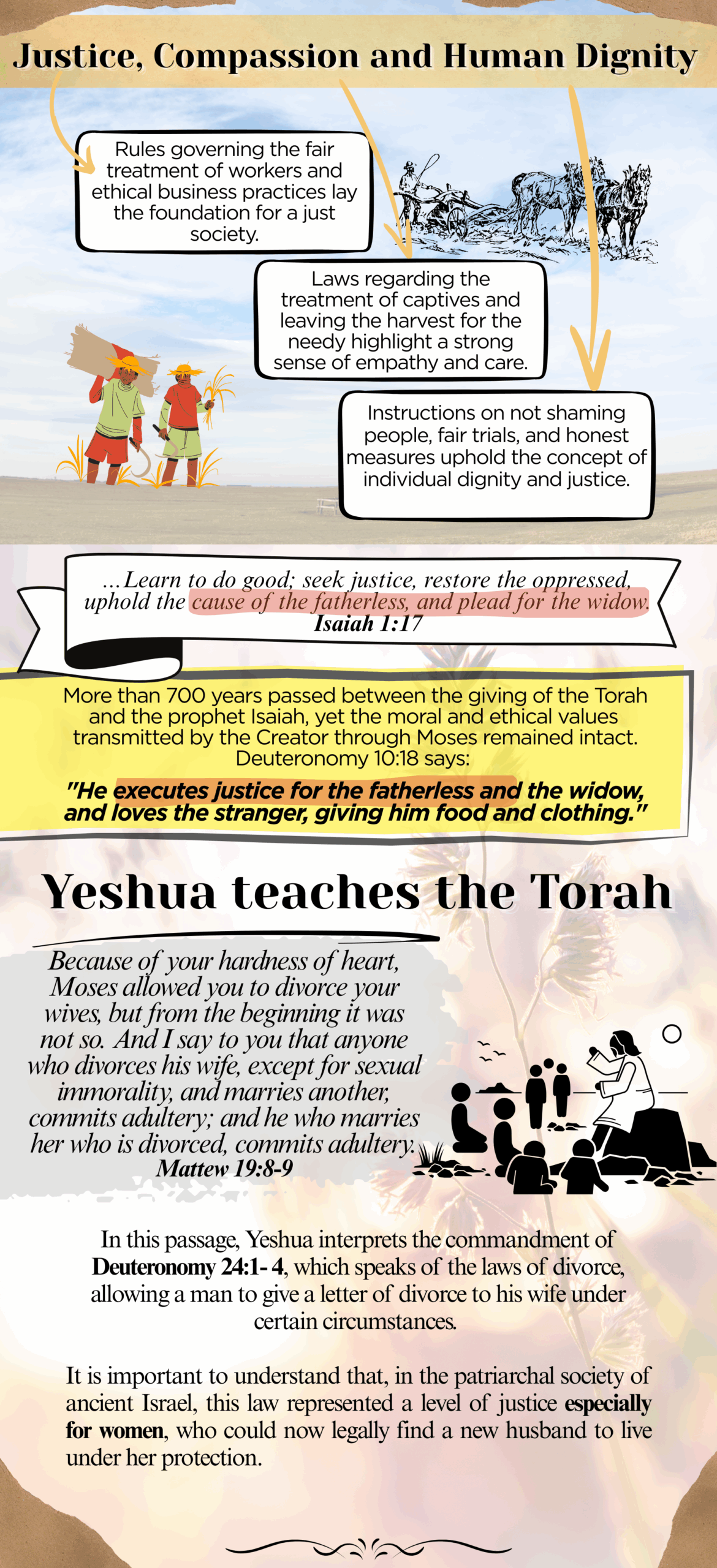

While many of these commandments constitute social laws that are no longer accepted within modern societies, it is essential to view them in the historical context of the Ancient Near East. In that cultural setting, a significant number of these ordinances represented genuine progress in the civil rights of vulnerable groups such as women and foreigners. Thus, what might appear to us as outdated or even harsh, in their time established a framework of justice that elevated the dignity of those who were otherwise marginalized.

In this way, these commandments provided the Israelites with moral and ethical guidance by embedding principles of justice and compassion into the fabric of daily life. For example, the injunctions to ensure just treatment of workers and to leave portions of the harvest for the poor not only safeguarded the welfare of these disadvantaged groups but also reminded the people of Israel of their covenantal responsibility before God.

The Stubborn and Rebellious Son

Many people who seek to discredit the Scriptures point to commandments such as the death penalty for the rebellious son, using it as proof that the Mosaic Law is an outdated and brutal system with no relevance in modern times. Yet it is important, as mentioned above, to place everything we read within its proper historical and cultural context.

Within the broader framework of the Torah, it is evident that all such cases were adjudicated through a judicial legal process, and were never taken lightly. In fact, we are told in Mishnaic times that a court which decreed even one death sentence during an entire generation (not only in relation to this commandment concerning the rebellious son, but regarding any commandment whose penalty was death) was considered to be a wicked court.

Questions for Reflection

How can I apply the teachings of justice and compassion from Parashat Ki Tetze in my daily life?

In what ways can we ensure that our business and labor practices reflect the principles of equity and fair treatment established in the Torah?

What specific actions can I take to protect and support the most vulnerable in my community, such as orphans and widows?