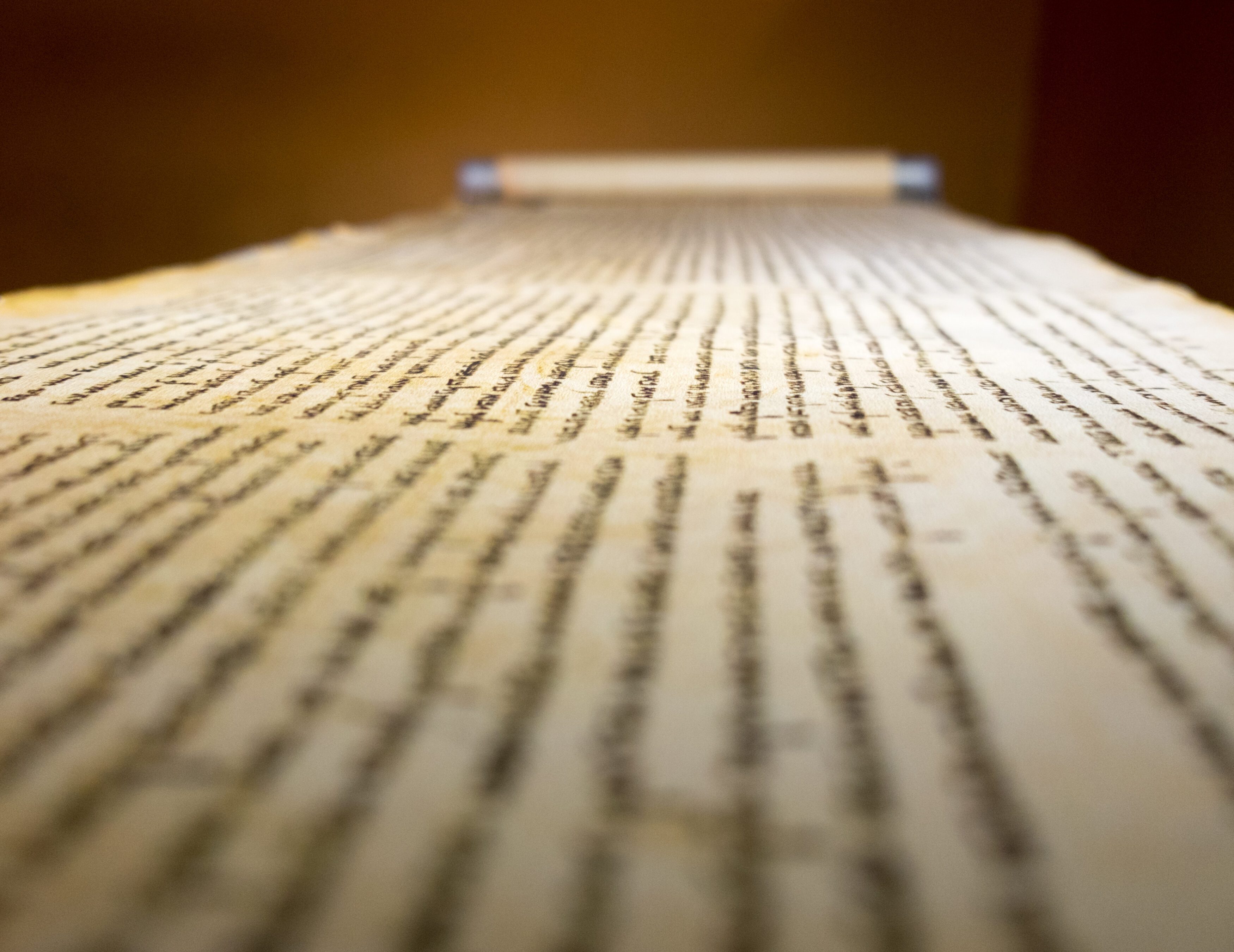

One of the oldest books found among the Dead Sea Scrolls in Qumran is the Book of Enoch.

The Bibles we have today include a compendium of books that were written at a particular period in history. The word canon, whose origin is generally traced to the Greek κανών which is a measuring rod, actually comes from the even more ancient Hebrew קנה (cané) which is a reed, and, precisely, was used for measuring. So we can deduce that the biblical canon refers to the group of books that have authority in terms of religious doctrine, whether in Christianity, Judaism, or Catholicism, whose respective canons differ from one another.

Needless to say, such authority in doctrinal matters was decided by the religious leaders of the time, so it is logical to attribute a certain subjectivity to such selection. Although most Christians consider the 66 books of their canon as the only “inspired” or “worthy of being taken as doctrinal”, the reality is that depending on the religious culture in which one has been raised, this will change. Just imagine that until before Martin Luther, works such as the books of Tobit or Judith would have been common knowledge.

How old are these books?

The biblical period covered by the apocryphal books is mostly limited to the Second Temple period, between the last prophets, concluding with Malachi, and the New Testament literature. This spans from around 300 BCE to 50 or 100 CE. There are later works from this time that were used by the so-called Church Fathers, but these would be included in another category as they relate exclusively to the New Testament and were written even after the closure of the Jewish canon in the 1st century.

One of the oldest books found among the Dead Sea Scrolls in Qumran is the Book of Enoch. This book, not included in the Jewish or Catholic canon, appears in more than ten different manuscripts in Qumran, written in what is believed to be the original Aramaic. Communities of believers in Syria and Ethiopia also preserved this book in their own languages (in Syria, Aramaic was spoken but had a different type of script, in contrast to the Essenes, who wrote Aramaic with the Hebrew letters we know today, which are originally Aramaic).

Other well-known works found in Qumran include the Book of Maccabees, Ben Sira, and Tobit.

Who decided which books entered the canon?

In the case of Judaism in Israel, a rabbinic assembly was formed, gathering in the city of Yavne around the year 100 CE. Although most writings in the Torah and the prophets were widely accepted, there was some controversy surrounding different books among the writings, such as the Song of Solomon and Daniel, the latter being written in Aramaic. One of the main reasons why many apocryphal books did not enter the Jewish canon was precisely because there were no Hebrew copies.

Other Jewish communities did not necessarily accept the authority of the rabbinic leadership in Israel and continued to use books they considered worthy of study. This is the case with the Ethiopian community of Beta Israel, which included, among others, the aforementioned books, the Book of Jubilees, the Testament of Abraham, the Testament of Isaac, and the Testament of Jacob.

The Catholic Church defined its canon at the Council of Rome in the fourth century, commissioning Jerome to translate the list of books into Latin. In the Eastern Church in Syria, different lists were maintained, and a unanimous decision regarding the canon was never reached. Some “extra” epistles found there include the Prayer of Manasseh and Psalm 151, while, for example, the Book of Lamentations is excluded.

During the Protestant Reformation, Luther decided to differentiate from the Catholic canon and moved seven books (Tobit, Judith, 1–2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, and Baruch), placing them in the Apocrypha section (“books not considered on par with the Holy Scriptures but worthy of being read and studied”). Despite moving them, at least he included and promoted their study. Unfortunately, this distinction paved the way for their eventual exclusion altogether.

Is it relevant to study these books?

If we limit ourselves to what Martin Luther said, then yes. Beyond Luther, it is worth delving into the historical context of each work. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls shed new light, confirming that Jewish communities of this time, even in the Land of Israel, considered many of these works worthy of study. In each of these books, we can appreciate not only ethical, moral, or spiritual messages but also the cultural environment of the Jewish people in a period of history that is unfortunately absent from our current Bibles.